Deported from New Jersey, a stranger in Jamaica: Man finds life hard back ‘home’

Fidel Napier made it out of Camden, often called America’s poorest and most dangerous city, only to end up in a country where the water sometimes cuts out and he fears for his safety when he leaves the house.

Almost six months have passed since federal authorities took Napier out of the Pennsauken home he shared with his wife and three kids, then left him in Jamaica, the country where he was born.

Napier came to Camden at age 5 but never became a US citizen. He was deported July 30 because of a 1998 drug conviction that labeled him a high-priority candidate. Napier, who once spent his time coaching youth basketball and going out to dinner with his wife, now lives with a distant cousin in St Thomas, a rural community outside of Kingston that this year was ranked as Jamaica’s most impoverished parish.

It is a foreign place to Napier. He does not have a Jamaican accent, which he said makes him stick out, and he can see people sizing him up when he’s in public. When friends send him money, he gives most of it to his cousin to help with bills. He is trying to obtain the identification documents he needs to apply for jobs, but given the area’s chronic unemployment, he’s not optimistic about his chances.

“I wake up every morning and think, ‘What am I doing here?’ ” Napier, 38, said in a phone interview. “I’m used to taking care of my family, being a father to my children. I just don’t feel like a man. This life, this isn’t me. It’s just not who I always tried to be.”

In his absence, his once-content suburban family home is roiled by sadness, anger, and stress, said his wife, Kiyonna Napier. Their 16-year-old daughter, Teyonna, complains of stomach aches and often asks to stay home from school. Taliah, their 13-year-old, cannot bear to have FaceTime phone calls with her father, bursting into tears at the sight of his smile. Their son, Fidel Jr., 7, has gone from cheery to standoffish, slamming doors and yelling.

“I’m having a tough time with them,” Kiyonna Napier told The Philadelphia Inquirer (http://bit.ly/1KynNL3). “They’re shutting down, they’re struggling. I’m struggling.”

Money is tight, she said. She took a medical leave from her job as a lab technician due to anxiety and depression that set in after the deportation. Responsibilities that were always shared, such as shuttling the kids between sports practices, now rest solely with her.

Friends pooled their money for a ticket so she could visit her husband once after he left, but the kids have not seen him since the summer. Hoping for a chance to spend the holidays together, the Napiers set up a donation website, gofundme.com/napierfamily, with proceeds going toward plane fare to Jamaica. So far the effort has drawn less than $250.

Napier’s deportation was the culmination of a process that began in 2010 when Homeland Security agents arrested him at the manufacturing company where he worked. After he was taken into custody in May, he spent weeks in federal detention before agents put him on a plane.

Policies enacted under the Obama administration focus on removing felons and repeat offenders from the country. It is unclear when Napier came to the department’s attention or why he was not targeted until more than a decade after his plea. The case against him stems entirely from crimes committed almost two decades ago.

Napier’s childhood in Camden was unstable, he said, and he turned to dealing drugs when he learned that Kiyonna, then his high school sweetheart, was pregnant. At 20, he pleaded guilty to selling cocaine. He now believes that getting arrested saved his life. After his conviction, he vowed never to abandon his family. He completed a drug program, served no prison time, and went on to build a career. In December, he and Kiyonna will mark 21 years as a couple.

“I always wanted my family together,” he said. “I didn’t want the mother of my children to raise them alone. I wanted to break that cycle.”

Napier has said he was unaware that the 1998 plea could jeopardize his status in the country, and that his lawyer at the time did not know he was not a US citizen. He appealed the deportation decision without success, arguing in one filing that because his stepfather helped police and federal agents arrest Jamaican-born gang members in Camden, a return to that country could put his life at risk.

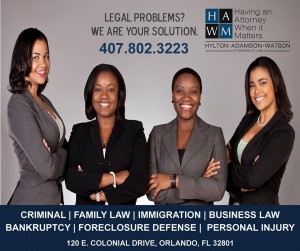

Kiyonna Napier said their attorney is applying for a “U” visa, a benefit that can be granted to victims of some crimes. Napier was shot at age 15 when he was near a gunfight in Camden, and the bullet remains lodged in his back. Though the application could take a year or more, Napier could qualify for the program, she said.

The Rev Tim Merrill, a minister who works with Camden’s youth and has mentored Napier for most of his life, said the financial hardship imposed by the deportation may eventually force the family to apply for public assistance.

“This has taken an ideal portrait of the African American family and shredded it,” he said. “There aren’t enough fathers that are with their kids, spending time with them every day and raising them like they should. And Fidel was one.”

Merrill also worries about the ripple effects.

“Here was a family I always looked at as a shining example of a success story,” he said. “Camden is a pessimistic city. To me, this sends a message that it is not enough to overcome hardship and do the right things. This reinforces that idea that success on the straight and narrow path is not attainable, no matter what you do.”